Stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus

Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose

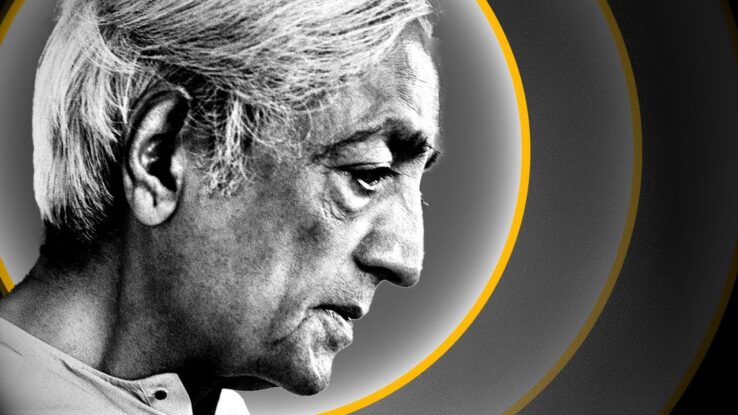

Reality is NOT What You Think – Jiddu Krishnamurti

What if how you view reality is wrong? I don’t mean this abstractly, I mean how you view the world and yourself at this very moment. And if reality is not what you think, what happens when you see it as it is? Can you see reality “as it is”, and what would that even mean?

Many sages, the Buddha first among them, point to delusion as the root cause of human suffering. To explore the mind’s workings and errors is no mere intellectual exercise. It is the key to freedom from suffering; to what we have come to call “liberation”, “awakening”, “enlightenment”.

But here we won’t be focusing on the Buddha’s teachings per se. We will be exploring a fresh formulation of the same insights by the philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti. Reading Krishnamurti has transformed my experiencing of life; here I’ll attempt to convey his most powerful teachings.

Since we will be exploring the nature of mind and reality, I invite you to approach this video as a guided meditation or self-inquiry. We will not be investigating some concept or object “out there”, but the nature of your present experience. So, take my words as pointers and test them against what you see as you observe your mind here and now.

Ready?

Thought, Language, and Virtual Reality

Let’s begin with a simple visual prompt. What do you see on-screen now?

Your most likely answer is “I am seeing the color red”. Let’s go with that and investigate it.

“I am seeing the color red” is, first of all, a thought, and a sophisticated one. This thought implies the concept of a color and knowledge of what the color red is. It implies, also, an idea of what it means to see something. If you think this is all basic stuff, try explaining it to one born without sight.

Most importantly, the thought “I am seeing the color red” presents experience as composed of a subject (“I”) and an object (“the color red”). This subject-object duality is an axiom of our thinking and talking about reality.

Now, I admit, mine was a leading question. By asking “What are you seeing”, I more or less dictate how you should answer. But then again, it is not I, but the very structure of language that dictates how we interpret experience. How many ways are there, after all, of asking somebody what they’re seeing?

Representing Reality?

Language forms as an extension of human thinking, but human thinking also arises as an extension of language. Language is the exterior and thought is the interior of one and the same phenomenon. That is, the mind’s activity of representing reality, what the Buddha calls nama, literally meaning ‘name’.

Nama is the whole complex of mental processes that interprets and represents reality. Nama is when you see this and think ‘I am seeing the color red’. Let’s explore how this naming of experience occurs.

What do you see now?

“A rose,” you will likely think. But is it you who think the thought “rose” or does the thought “rose” think itself? This may be an odd question but consider it for a moment.

Do you review all available names in your mind and pick the most appropriate one for the image on screen? Or does the name “rose” automatically arise as a conditioned response to the image? Can you see this image without automatically recognizing it as a rose?

Let’s try this again with a different image. Now rather than focusing on the image, observe how the mind reacts to it. Don’t force or suppress any reaction, just observe. Ready?

What do you see now?

Where is the Thinker of Thoughts?

Observe how the mind receives the image and automatically spits out a name, “chair” – a verbal or conceptual representation stored in memory. Do you find here a thinker who thinks the thought “chair”? Or is there just the algorithm of thought reacting automatically to stimuli?

Well, let’s not jump to conclusions. Even if you don’t manually select every thought, you do observe them all… right? The thinker, perhaps, is the one to whom thoughts appear. Let’s look into that.

Let’s return to our original prompt. What do you see?

The thought appears “I am seeing the color red” – we went over that. But now, who is observing that thought? As a matter of fact, who is seeing this red?

Pay attention now, this is a crucial point.

“It is I who experience, I who think, I who am!” Such is our core existential belief: “I think, therefore I am.” But what does this pronoun “I” refer to?

I can say I am Simeon Mihaylov. I can say I am a person, an individual, a subject, a self… But whatever I say I am, I am only substituting one representation (the pronoun “I”) with another. Now, all these representations, “I”, “self”, “person”, and so on – what are they representations of?

Caught in the Net of Language

Upon analysis, all representations ultimately represent other representations. This is true about the pronoun “I” as much as it is about the adjective “red” or the noun “rose”. We try to make sense of reality through our thinking and language… But all we ever think is what can be thought, and all we say is what can be said.

What and where is that reality we are supposed to be thinking and speaking about? Is there such a reality? Can we encounter anything that is not the product of thinking and language? Asking this very question is a product of thinking and language….

If there is a “real” reality beyond mental representations, that reality must be, well, unrepresentable. The best we can do, perhaps, is remain silent about it, as Wittgenstein recommends, and accept our existence in a world of representations…

Well, not quite. Enter Jiddu Krishnamurti.

What IS

Krishnamurti asserts there is a reality beyond the naming activity of the mind. What’s more, this reality is immediately available here and now. It is not something you get to through philosophy, meditation, or effort. It is either perceived immediately, or it is not perceived at all.

For obvious reasons, Krishnamurti refers to this reality beyond language with the most ambivalent words. Depending on the context, he calls it “the nameless”, “the real”, “the true”, and so on… Most often, he simply calls it “what is”.

So, what is what is?

The moment we approach this question philosophically, logically, symbolically, or by using any other function of thought, we’re back in the virtual reality of representations. Even to say reality is unspeakable is still to speak about it, to think it is unthinkable is to think about it, and to imagine it as unimaginable is still to imagine it.

Jiddu Krishnamurti on Stillness of Mind

Every movement of the mind, no matter how subtle, creates ripples of representations. These overlay what is with the conditioned activity of the mind and we end up caught up in that activity.

Krishnamurti says:

You may know the name of that flower, but do you thereby experience the flower? Experiencing comes first, and the naming only gives strength to the experience. The naming prevents further experiencing.

For the state of experiencing, must there not be freedom from naming, from association, from the process of memory?

J. Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living Series I

The mind then must be still for what is to be perceived. But how is this to occur? When asked “How can one go beyond thought?”, Krishnamurti replies:

One cannot go beyond thought, for the “one”, the maker of effort, is the result of thought… There is no ending of thought through compulsion, through discipline…

J. Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living Series I

The key to the stillness of the mind, Krishnamurti insists, is to not try to still the mind. Any attempt to end thought would only be the production of thought on a different level. Trying to think your way into what is is like trying to speak silence. You can say the word “silence”, but that is not silence, it is only a representation. The only way to “speak” silence is to not speak at all.

Jiddu Krishnamurti on the Flame & the Smoke

Krishnamurti writes:

The mind cannot think about something which is not of itself; it cannot think of the unknown… There is no relationship between this imponderable silence and the activity of the mind…

J. Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living Series I

If the thinking mind cannot experience what is, how then is what is to be perceived? Krishnamurti uses a striking metaphor to answer this question. He uses the image of “the flame” and “the smoke”.

By “the flame”, Krishnamurti refers to what is, the spontaneous, unrepresented state of Experiencing. By “the smoke”, he refers to the mind’s automatic representation of Experience.

Imagine looking at a sunset. Before your mind labels it as ‘beautiful’ or ‘orange sky’, there’s just pure seeing—the flame. But the moment you think about it, compare it to past sunsets, or try to describe it, the flame has become smoke.

“The flame” is always now. “The smoke”, whether representing past, present, or future, always relies on past impressions, on memory and conditioning. Hence, “the smoke” is always of the past. In fact, “past”, “present”, and “future”, exist only as categories of “the smoke”, only as representations. Time itself is an idea formed in “the smoke”. “The flame” is free of all reference to time. “The flame” simply is.

Before this gets too abstract, let’s bring it to our actual experience. Let’s return to our meditation objects.

Now keep your eyes on the screen and observe the mind’s production of names, images, associations… Do not pursue or push away any of these; simply observe. This is “the smoke”.

What’s more, the moment you recognize mental activity as “the smoke”, that’s just more mental activity, more smoke… Thought analyzing itself only creates more thought. We cannot dispel the smoke by blowing more smoke into it, so, again, how is the flame to arise?

Krishnamurti replies:

Find out; observe the smoke silently and patiently. You cannot dispel the smoke, for you are the smoke. As the smoke goes, the flame will come…

J. Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living Series I

Jiddu Krishnamurti & Choiceless Awareness

So, “observe the smoke silently and patiently”. Krishnamurti often calls this “choiceless awareness”, that is, awareness free of preference, free of desire. This, he maintains, is what clears the smoke, what stills the mind and allows for “the flame” to arise.

We’ve seen how thoughts arise automatically and how the sense of being the thinker or observer of these thoughts is also an automatic thought. To really understand what Krishnamurti means by “choiceless awareness”, and why it is the key to experiencing what is, we must explore the mind deeper. We must see what lies beneath thought.

Imagine the mind as an ocean. The surface of this ocean is constantly in motion, forming waves. This restless surface is the thinking mind with its representations. As Krishnamurti says:

The upper mind is only an instrument of communication…

J. Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living Series I

But what’s behind this instrument? We’ve seen you cannot be the one producing thoughts, as you are just another thought. What then produces them? This is an existential question, you see, as the answer to it will tell us what creates the thought “I” – what creates you.

Jiddu Krishnamurti on the Origin of Thought

A stone, for all we know, doesn’t think thoughts. Why have we, humans, evolved the thinking function? Krishnamurti’s answer to this agrees with what the Buddha taught some 2500 years ago. That is, sensation leads to desire, desire leads to attachment, and attachment leads to the arising of thought (and hence, of the thinker). Thought has evolved with the purpose of acquiring and prolonging pleasant sensations while avoiding unpleasant ones. It has evolved as an instrument of desire.

This is a lot to take in, so let’s go over it slowly.

How Desire Creates Thought

A stone, for all we know, has no sensory experience. Whether you caress the stone or crush it to bits, it makes no difference to it. Not so with humans. Our nervous system and sense organs allow for all kinds of sensations to arise. These sensations feel either pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral in degrees that run between bliss at one end and agony at the other.

Naturally, the organism seeks to acquire bliss and avoid agony. But this is a herculean task, as there is an infinite array of experiences you can have, and agony is always one slip away.

So, what does the organism do to increase its chances of bliss? It learns to remember what experiences bring pleasure and what bring pain. It develops memory. But to remember something is to store a mental image of it. Thus arises the representing function. The representing mind has to further differentiate between cause and effect – and so time develops as a category of thinking. Past, present, and future.

Finally, to make sense of its ever-changing perceptions, the mind develops the image of an unchanging entity separate from perceptions: the self. The entire process of thinking begins to orbit around this one image, what Jung calls the “ego complex”. Thus arises the sense of being an experiencer separate from experience, a thinker separate from thought.

This whole structure of the upper mind arises from the drive to move toward bliss and away from agony. Thought arises as an instrument of desire.

Desire & Thought

Let’s now return to our ocean simile. Beneath the waves on the surface, our thoughts, there is the undercurrent of desire. This undercurrent is what produces the surface activity of the mind with all its representations, including the ego, thought’s representation of itself.

Krishnamurti writes:

We name not only to communicate, but also to give continuity and substance to an experience, to revive it and to repeat its sensations…

[C]onsciousness is a process of naming or terming Experience, and then storing or recording it. It is this process that gives nourishment and strength to the illusory entity, the experiencer as distinct and separate from the experience… Thoughts create the thinker, who isolates himself to give himself permanency; for thoughts are always impermanent…

[What is] can come only with the absence of the desire for sensation; the naming, the terming must cease.

J. Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living Series I

So, it is not resistance to thought that stills the mind, as resistance is just a negative expression of desire and thus produces more thought. Thinking ends only with the cessation of desire.

But actually, why should we end desire, and hence thought? Isn’t it, after all, completely natural to pursue joy and avoid suffering? And isn’t it just as natural to think about how to do so?

Of course, we would think desire is natural. Thought arises as a function of desire and a dog won’t bite the hand that feeds it. But more importantly, there is a blindspot in our thinking, an obvious and common-sense fact the mind overlooks. It is this fact the Buddha points to when he explains why desire is the root cause of suffering. And that fact is: impermanence.

Impermanence and the Futility of Desire

Every source of joy we find in the world is on a trajectory of decay. Every pleasure, subtle or ecstatic, wholesome or decadent, passes before we know it. We ourselves are a stream of constantly changing perceptions. The mind tries to mask its own impermanence with the “self” construct, but soon enough the mind disintegrates, and so too does the imagined “self”. As Phra Khantipalo writes:

All compounds break down, all made things fall to pieces, all conditioned things pass away with the passing of those conditions… And we, living in the forest of desires, are entirely composed of the impermanent. Yet our desire impels us not to see this, though impermanence stares us in the face from every single thing around.

Phra Khantipalo, A Walk in the Woods

It is not in the best interest of desire to face its own futility and so it steers the mind away from reflecting on impermanence. Hence, we keep stumbling from one disappointment into another, seeking bliss in experiences, objects, and people that are forever changing, forever decaying and disappearing. You see now why freedom from desire is freedom from ignorance and suffering.

So, back to the question: How do we end desire?

The answer both Krishnamurti and the Buddha give us, 2500 years apart, is the same: We don’t end desire. Desire simply fades as the clear recognition of its futility emerges. Desire is ignorance of the nature of reality; and just as light dispels darkness, so too insight dispels ignorance. The truth sets us free.

The Freedom of Truth

Krishnamurti writes:

Awareness of the false as the false is the freedom of truth.

J. Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living Series I

And the Buddha, centuries earlier, says:

Ignorance is the one thing with whose abandoning ignorance is abandoned and clear knowing arises.

Avijja Sutta; SN 35.80

These may sound like circular statements, but that’s exactly their point. There is no special technique through which insight arises. See the false as false. See the ignorance of ignorance. It is this simple to be free of desire and delusion… But oh how difficult a thing the simple is.

Now we may better understand what Krishnamurti calls “choiceless awareness”. To be free of desire doesn’t mean to resist desire or to distract yourself from it. It doesn’t mean to think yourself out of desire with philosophy and logic. Freedom comes only with the awareness of desire as it arises, as it persists, and as it dissolves.

The Layers of the Mind

Let me now complete my imperfect simile. If the mind is an ocean, the restless water surface is the upper, thinking layer of the mind. This conscious activity is driven by the unconscious desire for bliss, the undercurrent beneath the waves. But if we sink deeper, we find the ocean bottom, the still, immovable foundation upon which everything rests. This base of the mind is what Krishnamurti calls “choiceless awareness”. It is the ever-present fact of aware experiencing here and now.

If the mind consisted only of desire and thought, there would be no escape from suffering and ignorance. But prior to thought and desire, there is the mind’s bedrock of pure experiencing. “Choiceless awareness” is not some mystical or transcendent reality. It is also not something you can see or experience, as it is the very fact of seeing and experiencing – here and now.

Krishnamurti: Choiceless Awareness and What IS

Krishnamurti writes:

The mind and what is are not two separate processes, but naming separates them. When this naming ceases, there is a direct relationship…

Then the mind is only the state of experiencing, in which the experiencer and the experienced are not…

J. Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living Series I

“Choiceless awareness” and what is are not two separate things. The former is not a technique for getting the latter. As Krishnamurti writes:

Nothing is essential for stillness but stillness itself… There are no means to silence; silence is when noise is not… See the truth of this, and there is silence.

J. Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living Series I

But if experiencing reality beyond thought is so simple and available, why is it so difficult for us? Well, it is difficult because it is so simple and available. It is too simple for understanding to understand, and too available for desire to desire.

What is is not something you can acquire and get pleasure from. In fact, when it is, you are not. Choiceless awareness is not a skill you can impress your friends with, nor is it an exciting experience. It does not make you rich, smart, good-looking, or famous.

About the only thing it does do is end ignorance and suffering. But we will justify our ignorance and suffering a million times before we’ve had enough of them.

Jiddu Krishnamurti, the Buddha, and Jesus Christ

Remember, all I’ve said here about what is, and all Krishnamurti, the Buddha, and others have said about it, is not what is.

Directly experiencing reality beyond our thoughts and desires happens only when… well, when we experience it directly. It is not something one person can give to another. What is can be pointed to, but all directions to it, if taken literally, are misdirections.

Humanity’s great teachers find fresh ways of guiding us to what is, but our instinct is to latch onto the guidance, the teaching, rather than pick up our cross and see what only our own eyes can show us.

When Christ proclaimed

I am the way and the truth and the life.

John 14:6

I don’t think he was referring to himself as a historical individual. I think he was referring to the eternal way, truth, and life, which is to be found in the immediate “I am”. Breaking all rules of thought and language, Christ identified himself with that timeless reality saying:

Truly, truly, I say to you, before Abraham was, I am.

John 8:58

Being What IS

This is a revelation each one of us must arrive at by ourselves. The Buddha instructed his disciples on his deathbed:

Be islands unto yourselves, refuges unto yourselves, seeking no external refuge; with the Dhamma as your island, the Dhamma as your refuge, seeking no other refuge.

Maha-parinibbana Sutta; DN 16

Notice here how the Buddha equates being your own island with having the Dhamma (“the Way”) as an island. Like Christ, he is articulating that highest realization where there is no distinction between I and what is.

And how is one to experience this highest realization? The Buddha gives the same guidance as what Krishnamurti calls “choiceless awareness”. He says:

When he dwells contemplating the body in the body, … feelings in feelings, the mind in the mind, and mental objects in mental objects, earnestly, clearly comprehending, and mindfully, after having overcome desire and sorrow in regard to the world, then, truly, he is an island unto himself, a refuge unto himself, seeking no external refuge; having the Dhamma as his island, the Dhamma as his refuge, seeking no other refuge.

Maha-parinibbana Sutta; DN 16

To see how the great Christian mystic Meister Eckhart presents these same insights, I invite you to my earlier video on him. Thank you for watching and consider sharing this content if you find value in it.