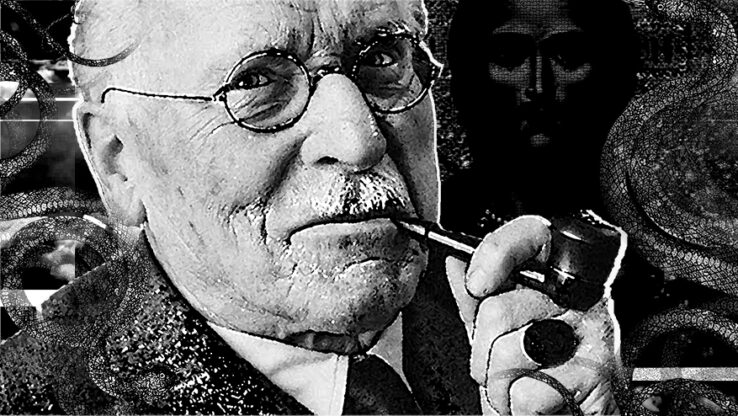

The Swiss psychologist Carl Jung is among the deepest souls to have blossomed in the garden of human history. To read his work is to embark upon a richer, deeper, and more mysterious relationship with reality. Yet even Jung’s most obscure doctrines hold an undeniably human quality.

Today, we take a look at a beautiful passage that encapsulates a core tenet of Jung’s philosophy. The passage comes from a lecture he presented to a group of clergymen and begins by discussing the relationship between a psychologist and their patients.

However, Jung quickly arrives at a far more fundamental relationship. The single most important one we can have.

Read on to find out more…

Jung’s Appeal

… People forget that even doctors have moral scruples, and that certain patients’ confessions are hard even for a doctor to swallow. Yet the patient does not feel himself accepted unless the very worst in him is accepted too. [This] comes only through the doctor’s sincerity and through his attitude towards himself and his own evil side.

If the doctor wants to offer guidance to another, or even to accompany him a step of the way, he must be in touch with this other person’s psychic life. He is never in touch when he passes judgement. Whether he puts his judgements into words, or keeps them to himself, makes not the slightest difference. To take the opposite position, and to agree with the patient offhand, is also of no use, but estranges him as much as condemnation.

We can get in touch with another person only by an attitude of unprejudiced objectivity. This […] is a human quality—a kind of deep respect for facts and events and for the person who suffers from them—a respect for the secret of such a human life.

The truly religious person has this attitude. He knows that God has brought all sorts of strange and inconceivable things to pass, and seeks in the most curious ways to enter a man’s heart. He therefore senses in everything the unseen presence of the divine will. This […] is a moral achievement on the part of the doctor, who ought not to let himself be repelled by illness and corruption.

We cannot change anything unless we accept it. Condemnation does not liberate, it oppresses. I am the oppressor of the person I condemn, not his friend and fellow-sufferer. I do not in the least mean to say that we must never pass judgement in the cases of persons whom we desire to help and improve. But if the doctor wishes to help a human being he must be able to accept him as he is.

And he can do this in reality only when he has already seen and accepted himself as he is.

Matthew 22:39: Thou Shalt Love Thy Brother…

Here we reach the heart of Jung’s insight. No matter the context, whether you are a psychologist, a clergyman, a friend, a partner… You can never build a truly authentic relationship with another unless you realize that everything shameful, frightening, and ugly within them lives within you also.

This, of course, is the meaning of compassion, coming from the Latin compati (com ‘together’ + pati ‘to suffer’).

True compassion is knowing another’s struggles as your own.

Yet the first step towards succh moral maturity is not a step towards the other. It is a step towards oneself.

Jung continues…

Perhaps this sounds very simple, but simple things are always the most difficult. In actual life it requires the greatest discipline to be simple, and the acceptance of oneself is the essence of the moral problem and the epitome of a whole outlook upon life.

That I feed the hungry, that I forgive an insult, that I love my enemy in the name of Christ—all these are undoubtedly great virtues. What I do unto the least of my brethren, that I do unto Christ.

But what if I should discover that the least amongst them all, the poorest of all the beggars, the most impudent of all the offenders, the very enemy himself—that these are within me, and that I myself stand in need of the aims of my own kindness—that I myself am the enemy who must be loved—what then?

As a rule, the Christian’s attitude is then reversed; there is no longer any question of love or long-suffering; we say to the brother within us “Raca”, and condemn and rage against ourselves. We hide it from the world; we refuse to admit ever having met this least among the lowly in ourselves.

Had it been God himself who drew near to us in this despicable form, we should have denied him a thousand times before a single cock had crowed.

Meeting The Shadow

Jung’s language here is laden with Biblical allusions – understandable, considering his audience. But what he is getting at is something as simple as it is universal.

Alan Watts called it the ‘element of irreducible rascality‘ within us – Jung called it the Shadow.

The Shadow is that autonomous subpersonality within us made up of all the thoughts and feelings we are ashamed of having. The harsher we judge ourselves – the deeper and stronger the Shadow grows.

The Shadow is a cross we all carry within ourselves, whether we know it or not. It holds great danger – but so does it offer great opportunity.

The danger of the Shadow is its ability to possess us and make us hate in others those things we cannot accept in ourselves.

Treasures In The Dark

But the Shadow is also a great treasure. It allows us to understand the irreducible darkness of the world not only intellectually but experientially.

As Jung reminds us, to accept oneself truly is the supreme moral achievement. We can accept others only to the extent that we have managed to accept ourselves.

It is in the difficult soil of our all-too-human garden where we must cultivate the fruits of love, compassion, and understanding. Only by growing these within can we offer them without.

No wonder the New Testament presents its supreme ideal as God incarnate in man. And no wonder Buddhist cosmology presents human life as preferable to being reborn as a heavenly being.

Why?

Because only a deep immersion in the human condition can bear the fruit of understanding.

Only understanding, only comradery in the struggle of the human heart can bring about true compassion.

So you see how the degree of compassion you show others is a direct measure of the road you have traveled within yourself.

This is the essence of Jung’s appeal.

Turn your gaze within. See the ugliness, pettiness, violence, and brokenness there. Don’t look away.

These are not your captives, nor your enemies.

These are visitors from the beyond – children and teachers come to teach you what is love and humility.

Very interesting artwork happy to have found this space.. much metta

Thank you, I appreciate this!