Jung vs. Buddha On The Unconscious

The work of Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung and the ancient teachings of Gautama Buddha seem to belong to different worlds. They originate from completely different cultures, millennia apart, and two opposite ends of the Earth. Yet something more fundamental than these differences unites them. That is, the conviction that man’s well-being is rooted in the mind and that to understand the mind is the key task of maturity.

This shared interest in the psyche led both Jung and Buddhism down similar paths of investigation. Sometimes they reached similar conclusions, sometimes they didn’t. But both discovered there is much more to the mind than people realize. Both arrived at what today we call the unconscious.

In this article, we’ll compare the Jungian and the Buddhist concepts of the unconscious. But not in a dry, scholarly way. This article will be a success if by the end you have gained some insight into your own mind. So, with this goal in mind, let’s jump right in.

But before we get to the unconscious, let’s start with consciousness.

(You can watch the video version of this essay on YouTube.)

Buddhist Consciousness

The Buddha’s view of consciousness is quite different from what most Westerners are familiar with. To him, consciousness is a phenomenon that arises when sense organs and sense objects come into contact.

Now what does this mean?

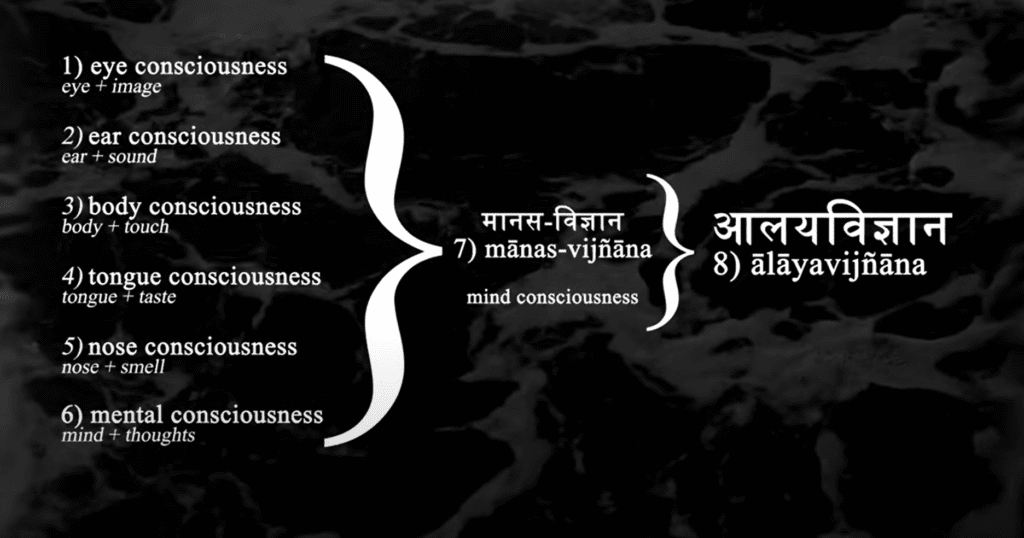

The sense organs are six. There are the five we know in the west: eyes, ears, tongue, skin, and nose. But in Buddhism the mind counts as an additional (sixth) sense organ. The corresponding sense objects are images, sounds, tastes, feelings (as in touch), smells – and thoughts.

Observe how here a thought is not something the mind produces, but something that appears to the mind. If we feel our thoughts are ‘our thoughts’, originating from our ‘selves’, this is as unenlightened as thinking the sounds we hear originate in our ears. (Tinnitus aside.) Much of the Buddhist practice of meditation is aimed at breaking our habit of identifying with thoughts.

If you want to learn more about this, I suggest you check out our earlier article on the no-self.

Locks & Keys

Anyway, you can think of sense organs as locks and of sense objects as keys. When the right key goes into the right lock, the doors of perception open. Consciousness arises.

This model is extraordinary for at least two reasons.

First, it presents consciousness without any notion of a subject or a self. Buddhism compares consciousness to fire. Fire is not an independent ‘thing in itself’. Fire depends on fuel to burn. If there’s no fuel, there can be no fire. In this same way, if there are no appropriate sense objects and sense organs present, there can be no consciousness.

Compare this model with all those wisdom traditions that view consciousness as a primary essence. As some spiritual reality that exists independently of time and space. Immediately you will see how controversial the Buddha’s theory of mind was. And it still is.

There’s another profound implication of this model.

The World Of Experience

Our six sense organs can each only match with one type of sense object. For example, the eye cannot perceive smells, nor can our skin feel colors. But there is no reason to assume that the six types of sense objects we perceive are the only ones that exist!

For example, a plant doesn’t have a sense organ for thoughts, and a mushroom doesn’t have a sense organ for sights.

To these types of organisms, the world appears in entirely different ways.

This would mean that the world of our everyday experience is not objective in the least. It is rather the product of what our bodies are able to perceive with their limited sets of sense organs. A blind man walking through the Louvre would see nothing. But this nothing is and remains his reality. It is no less true than the reality of a sighted person enjoying the works of art.

In this sense, there is little difference between what we call ‘the world’ and what our bodies are able to process and construct in our awareness. We can ever only experience the limited representation of reality our bodies are able to generate. The Buddha goes so far as to say our bodies are our world. He says:

In this fathom-long body, with its perceptions and thoughts, I proclaim the world to be…

The Buddha, Rohitassa Sutta

Subject vs Object?

This obviously goes against the whole subject-object distinction we take for granted in the West.

Or as Lord Byron writes:

Are not the mountains, waves, and skies, a part / Of me and of my soul, as I of them?

Lord Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: Canto 03

The point here is that the universe of which we are a part has endowed us with limited resources to perceive it, let alone understand it. Our clearest perception of the world can ever only be a low-resolution representation of it. In effect, a new, private reality. What would mountains, waves, and skies be if there was no consciousness to perceive them as such?

The great presocratic philosopher Heraclitus had much to say about how our perception creates our world. Check out our article on him to learn more.

The illusory feeling that humans perceive an objective, external reality comes from the circumstance that the only entities with which we can discuss reality are yet other humans. And we all have the same hardware and software.

If any among us get funny ideas about what reality is, we put them away in asylums for the insane. But the only real argument in favor of the sane versus the insane is that the former outnumber the latter.

Reportedly.

A desperate argument if ever there was one.

Beyond Consciousness

Anyway, here Jung would say ‘Okay, but…’

Imagine a boy whose mother is cold and unloving. This boy grows up and every time he meets a woman, he goes out of his way to please her. Or he takes the most innocent comment from her as an offence aimed personally at him. So even after the grown man’s mother is no longer present, the sight of a woman triggers his childhood behavior.

How can this be explained by the theory of sense organs and sense objects? If the keys that once unlocked certain traumas are no longer present, how do these traumas keep arising?

The disciples of the Buddha too came across this problem in their own way. It became most obvious for the Buddhist school of the Yogācāra, which consisted of the most advanced meditators the world has ever known.

What Is The Source Of The Stream?

The Yogācāra monks could enter such deep states of meditation that their stream of consciousness would come to a halt and all mental afflictions would disappear. This way they extinguished the three Buddhist fires of desire, hatred, and ignorance.

The problem was, these states never lasted.

As soon as they were out of meditation, the monks discovered they were back to their ordinary, unenlightened selves.

But how can desire, hatred, and ignorance reappear after they have been extinguished? And how can one’s stream consciousness reemerge in the first place once it has stopped?

Or if we take dreaming as a Jungian example, how and where does our consciousness return from when we awake?

For both Jung and the Yogācāra Buddhists these kinds of questions pointed in the same direction.

Consciousness alone is not sufficient to account for human experience. There must be some additional region of the mind which remains active even when consciousness dissolves. This background region must be what connects and keeps track of all our momentary experiences.

Jung And Buddhism On The Unconscious

The Buddhists called this background of the mind the ālayavijñāna, meaning store-house consciousness.

Jung called it the unconscious. He described it like this:

‘Everything of which I know, but of which I am not at the moment thinking;… everything perceived by my senses, but not noted by my conscious mind; everything which, involuntarily and without paying attention to it, I feel, think, remember, want to do; all the future things that are taking shape in me and will sometime come to consciousness; all this is the content of the unconscious.’

C.G. Jung, On the Nature of the Psyche

For both Jung and the Yogācāra Buddhists, the unconscious is like what modern physicists call dark matter. It is not something anyone can observe directly (otherwise it would be conscious), but it must exist to account for the facts of reality. If this strikes you as a desperate argument… you’re right. Our best attempts to understand deep reality can ever only be such: desperate.

You Are Made Of The Unconscious

So what does the unconscious account for?

Well, how about… you! A self can only exist because of the unconscious. Let me elaborate.

Consciousness is momentary. For example, clap with your hands and listen to the sound. Well, you were conscious of that sound for a moment there, but now it’s gone. Now only the memory of the sound remains and soon it too will fade. This applies to all experiences you’ve ever had.

If you had only your consciousness, there would be just a ceaseless stream of disconnected experiences without any narrative that connects them. Your mind would be like a pot with the bottom taken out. No matter how much experience is poured into it, it would remain empty of concepts like ‘self’ and ‘world’.

This insight comes from the Yogācāra Buddhists. They understood the sense of being a separate self is a story we tell ourselves based on a reservoir of experience we accumulate through life. And where is this reservoir stored? Not in consciousness, that’s for sure; consciousness is the momentary contact of sense organs with sense objects. So, our past experiences must be recorded in an ālayavijñāna, an unconscious storehouse of the mind.

Before we continue, I want to thank everyone who supports my work! These pieces are the fruits of my personal journey, and each one takes me over a month of work. If you’re finding value here, you can support my work by joining our community on Patreon. This will also give you access to exclusive content, community events, and the ability to submit your questions for guests on my podcast. Thank you for your support!

The Yogācāra Model Of The Psyche

Let’s sum-up the Yogācāra model.

Conscious experience occurs when any of the six sense organs come in contact with their corresponding sense objects. These six streams of experience are stitched together into one coherent picture of the world through a seventh type of consciousness. This is called the mānas-vijñāna (meaning ‘mind consciousness’).

In Jungian terms, the mānas-vijñāna is the ego, the sense of being a self that is experiencing a world.

The ego is vital for making sense of the world even if it leads us to all kinds of deluded behavior. After experiences get conceptualized and related to the ego, they finally sink down into the ālayavijñāna, the unconscious storehouse of the mind. There, they remain dormant until the right conditions trigger them to arise to the surface of consciousness.

The Yogācāra Model Explained

Let me give an example of how this works in real life.

A boy bullies others at school. The mānas-vijñāna extrapolates from these experiences a sense of self that is sadistic and seeks power over others. This gets imprinted into the storehouse of his mind.

When the child grows up, he enters the corporate world. There, he sees how people in power can bully their subordinates in all kinds of subtle ways. This triggers his childhood memories from the ālayavijñāna and inspires him to climb the corporate ladder so he can have power over others.

Eventually, he becomes a tyrannical boss and reinforces his sadistic sense of self. These new experiences sink into his unconscious and make it even more likely he’ll repeat this behavior in the future.

The Evolution Of A Self

The Buddhists compare this process to how rainwater gathers in channels on the ground. The more time passes and the more it rains, the deeper these channels get. Finally, they turn into rivers. This is how with time our actions become habits and our habits become our ‘selves’.

Buddhists also use seeds as a metaphor. Our unconscious is like the soil and our actions and experiences are seeds that get planted there. When the right conditions arise, these seeds ripen into new actions and experiences. This explains how our past stays with us and determines our present and future.

A psychotherapist would inquire into your childhood; a Buddhist would inquire into your past lives. Whether you call it trauma or karma, the principle is the same.

This is some profound insight into the human psyche, but… There’s something missing. And Jung would be the first one to point it out. He discovered an additional aspect of the unconscious the Buddhists never came across.

Unconscious Compensation

Let’s take our previous example of the bully that becomes a tyrannical boss.

One night that man has a horrible dream. In his dream, he walks into a room of mirrors. In each mirror, he sees his reflection committing terrible acts of violence. The man wakes up from the dream horrified. For the entirety of the next day, he can’t shake off a feeling of guilt. He starts observing his behavior at work and, to his shame, discovers just how much of a jerk he is towards everyone.

Now this is a made-up example, but I think we can all relate to it. Our dreams sometimes show us uncomfortable truths about ourselves that we either can’t or won’t face in our waking lives.

Jung called this unconscious compensation. What he meant was that our unconscious seeks to balance the activity of our conscious mind. Borrowing from Newton, Jung tells us every conscious action causes an equal and opposite in direction reaction in the unconscious.

Someone who acts violently could have dreams that confront him with suppressed feelings of guilt. On the other hand, someone repressing her anger could have dreams that encourage her to stand up for herself more.

If you’ve ever paid attention to your own dreams, you will know this occurs. And yet the Yogācāra model of the mind overlooks this entirely.

In the Yogācāra view, the unconscious simply stores and amplifies experience. Seeds of wrath produce grapes of wrath. But as we can see from our dreams, sometimes the unconscious flips conscious experience on its head.

I think there’s an important reason why Jung understood this but the Buddhists didn’t.

Attitudes To The Unconscious

You see, the Yogācārins were only concerned with how to end the unhealthy habits supported by the ālayavijñāna. Beyond that, the unconscious was of no interest to them. They knew how one can purify consciousness here and now. But to put an end to suffering for good, they wished to learn how to cleanse the unconscious.

That’s as far as their interest went.

Jung, on the other hand, saw the unconscious as a source of wisdom and guidance. He knew it contained much more than waking consciousness and he wanted to learn from it. This attitude led him in a direction the Buddhists never thought to go. It made him ask one of his deepest and most controversial questions.

Jung asked: If consciousness dreams and sinks into the unconscious… could the unconscious also dream and sink into an even deeper unconscious?

It was this strange question that led Jung to his greatest discovery.

The Collective Unconscious

The collective unconscious is such a deep and controversial idea that to go into it would make this article twice as long as it already is. But we cannot leave it out completely either.

Remember how Jung and the Buddhists discovered the unconscious? They observed that consciousness itself is too limited to account for all its contents. The conclusion was that these contents must be coming from somewhere else – some deeper and hidden region of the mind.

Well, Jung continued this same reasoning one step further.

He observed his patients’ dreams mostly referred to their personal experiences, like our example with the bully. That’s to be expected. But to Jung’s amazement, sometimes his patients dreamt of things that had nothing to do with their personal lives. Sometimes their dreams contained obscure elements from world culture and literature. Ancient gods, alchemical images, Mesopotamian myths… How could people dream of things they had no knowledge of?

The more dreams he analyzed, the more convinced Jung became. There must be an even deeper region of the mind under one’s personal unconscious. This region somehow contains all that has ever been experienced by the human mind and it is common to all people. Perhaps even, it is common to animals too.

Jung called this the collective unconscious. A great storehouse of psychic content that is the birthplace of all our individual psyches.

The Collective Self

Because we are connected in such a way, everything an individual can experience can be experienced also collectively. The Enlightenment, the Nazi movement, the Protestant revolution… These are all examples of how large groups of people can act as a single individual possessed by an idea or an emotional state.

The collective unconscious is a network in which we are all connected. Our actions both arise from and contribute to the network of all individual minds.

This is obviously a controversial idea. And it would have terrified the Buddhists.

Not only is there one’s consciousness that must be liberated… and not only must one’s unconscious be liberated… But there’s also the collective unconscious of all sentient beings that must be freed from suffering.

How could you possibly heal the collective karma of all sentient beings?

The Bodhisattva Vow

Well, perhaps, on some level, the Buddhists did understand this. This would explain the bodhisattva vow.

In the Mahayana tradition, a monk vows to delay his own enlightenment until the day all sentient beings are liberated from suffering. He vows:

The unrescued I will rescue

The unliberated I will liberate

The uncomforted I will comfort

Those who have not yet reached [final]nirvana, I will cause to attain [final]nirvana

The Bodhisattva Vow

Mahayana Buddhism recognizes its project can never succeed if even a single sentient being remains in ignorance and suffering. Is this an intuition of what Jung called the collective unconscious?

I believe all the world’s mystics teach us that on some deep level we are all like leaves on a tree. The many leaves create the illusion of many beings. But in the end, there is only the one, only the tree living itself through each of us. We must credit Jung with his serious attempt to give a scientific expression to this idea. No wonder his critics accused of mysticism.

Conclusion

We’ve covered lots of ground here, but really, we have just scratched the surface of both Jungian and Buddhist theory of mind. We’ve not even mentioned the Jungian archetypes and complexes or explored Buddhist karma and rebirth. I leave these for future articles.

I hope you walk away from this knowing your mind is much more mysterious and complex than it seems. And what you call ‘I’ is but the tip of an iceberg that goes so deep it might end up being what we call ‘God’.

Thanks for this article!! It confirms and explains resent thoughts and insights I was getting about the unconscious mind. How the right conditions can trigger old behaviors that I thought were gone and I wouldn’t repeat. Even how the collective consciousness affects all of us. I have been been wrestling with all of this and you explained and confirmed some of my thoughts. Appreciate you!!!

How do you purify the unconscious mind? I have healed and come a long way from where I was but I would like to go further.

Thank you Darrin, I’m glad you enjoyed the piece! I find Ken Wilber quite enlightening in relation to your question. He insists that inner work must both focus on the depths (shadow work, therapy, journaling, depth psychology, etc.) and on the heights (meditation, yoga, non-duality, Buddhism, etc.). In other words, we must take care of our basement and foundations (the personal and collective unconscious), while also building our house to greater height (the transpersonal, non-self dimension). I really recommend reading him if you have not. You can start with A Brief History Of Everything.

Thank you!!! Never heard it put like that very interesting. I do and practice some of the things you mentioned. Because of your articles I have already read Dark night of the soul by Gerald May and I have Escape from Evil by Becker. Haven’t read it yet but looking forward to it and the one you mentioned above.

Keep shining the light brother!!!

Thank you for encouraging words! I’m glad to hear the work has brought you something of value 🙂 Let me know what you think of Escape from Evil when you get to it. This and Becker’s other masterpiece (Denial of Death) are two of the deepest, most powerful books I’ve read.