The Noble Eightfold Path of Buddhism is, simply put, the path to nirvāṇa. It is the teaching put into practice. To walk this path all the way is to reach awakening and liberation.

The Buddha did not leave behind vague instructions on how to reach nirvāṇa. He did not make general statements like ‘Be a good person’ or ‘Live in harmony’ or ‘Have faith’.

No. The Noble Eightfold Path is a detailed, step-by-step guide on how exactly to perfect your life and transform your mind.

You would think there’s nothing more exciting than learning this guide…

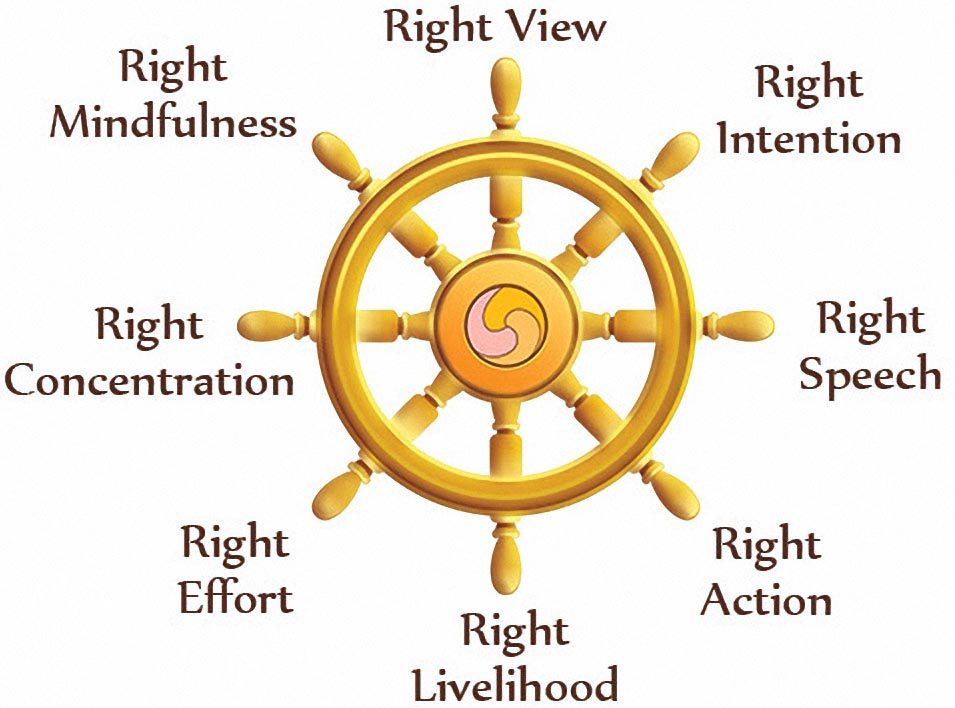

Sadly, most study resources on the Path are either superficial or boring. They usually start with an image like this one:

They list the eight components of the path and perhaps they tell you it is divided in three sections: Ethics, Mental Practice, and Wisdom.

Then they go on to tell you what you shouldn’t do and what you should do.

This can be off-putting and uninspiring, which makes it misleading too. The Buddha’s original teachings had the opposite effect of drawing in his listeners. Many became his life-long disciples after hearing just a single talk.

If learning about the Path does not shake your entire worldview, you’re not learning it right.

So, let me try something different.

In His Own Words

I want to let the Buddha present the Noble Eightfold Path to you. I’ll do this by telling you a story. Not one I made up, but a Buddhist sutta dating back some 22 centuries.

I mean The Shorter Elephant Footprint Simile Sutta.

I know – not the catchiest title, but it helped cataloguing and memorising the canon when the tradition was still oral.

In fact, this is one of the most fascinating texts I’ve ever read. Here we find the Buddha himself present the Noble Eightfold Path to an outsider. The outsider comes confused, uncertain whether the Buddha is a true teacher or a fake guru. At the end of the sutta, he is no longer confused.

In any case, I’ll interrupt the story frequently, to give you some commentary and context to what the Buddha is saying. I hope this will be useful.

Now let’s hear about this Path of the Buddha – from the Buddha.

(You can watch the video version of this essay on YouTube.)

I present to you The Shorter Elephant Footprint Simile Sutta.

A Chance Meeting

One day, the brahman Janussonin was traveling in his chariot. It happened that he came across a friend of his, the wanderer Pilotika.

After the two men exchanged greetings, Pilotika said he had just been in the presence of the teacher Gautama. Gautama, of course, was he who people called ‘the Awakened One’ – the Buddha. He had been causing quite the excitement lately with his talks.

Being of the priest caste, Janussonin was well-versed in the philosophy and religion of the time. He had learned to not get too excited about gurus, as new ones kept popping up all the time. Each, of course, claimed to possess ultimate knowledge.

So, Janussonin asked his friend:

‘How do you judge him, Pilotika, is this Gautama as wise as they say?’

‘I am not nearly as wise as him to judge of his wisdom,’ Pilotika answered.

‘This is high praise coming from you,’ Janussonin said. And his friend replied:

‘Who am I to praise Gautama? He is praised by those we praise as the best of beings, human and divine.’

This piqued Janussonin’s interest. It probably annoyed him a little too.

‘Come now,’ he said, ‘how can you be that certain of the man’s wisdom?’

Pilotika was silent for a moment. Then he said:

‘Suppose an elephant hunter were to enter the forest and were to see there a large elephant footprint. By this he would know a great bull-elephant lives in the forest. In the same way, I saw not one, but four footprints in the teacher Gautama. Thus, I came to understand he is truly self-awakened, he teaches the true path correctly, and his disciples practice rightly’.

‘Let me tell you of these four footprints,’ Pilotika continued. ‘I saw great intellectuals, skilled in debate, like hair-splitting marksmen. They seek and destroy philosophical positions for sport. When they learn the teacher Gautama is visiting a village or a town, they make ready to attack his teaching. They prepare their questions and anticipate his answers. On every point, they prepare arguments against Gautama. They go to him then, and he gives them a talk on the Dhamma. When he is done speaking, they don’t even ask him their questions. As it turns out, they become his disciples. I saw such intellectuals from the warrior caste, from the priest caste, from the householder caste, and from among the contemplatives. In all four cases, the wisest among the wise were left speechless. They left their homes and families and followed Gautama. These are the four footprints I saw.’

Janussonin was rather intrigued by this tale. Perhaps he felt somewhat challenged too. After all, he himself was a man of learning. Could this Gautama really be so smart and wise?

Janussonin thanked his friend and decided he must visit the teacher himself.

Ok, let’s pause here.

The Elephant Footprint

What are you doing right now? You’re reading this article to learn about the Buddha’s teaching.

Perhaps you are like Janussonin, a newcomer who wants to see what Buddhism is about.

Or perhaps you are like those intellectuals who seek weak points in the Dhamma. I imagine these like ancient Indian versions of Jordan Peterson or Christopher Hitchens.

Or maybe you’re like Pilotika, already convinced of the Buddha’s wisdom and you’re here for sheer enjoyment of the Dhamma.

In any case, this story begins with you and me. It begins with all of us elephant hunters who enter the forest in search of Truth.

Janussonin is us.

His meeting with Pilotika is the elephant footprint he discovers. Perhaps this article is this same footprint for you?

Now back to the story. We pick up some time later when Janussonin has made his way to the Buddha.

Meeting The Master

‘Many blessings upon you,’ Janussonin said and bowed to the famous teacher.

The two men exchanged greetings and courtesies, all according to etiquette. Then Janussonin sat by Gautama. He told the teacher of his conversation with Pilotika, recounting each word carefully. When he finished, he fell silent. He couldn’t remember whether he had a question he wished to ask.

In a few moments, it was Gautama who spoke. The teacher said:

‘Pilotika’s simile of the elephant footprint is incomplete. I will complete it for you, listen closely.’

Janussonin was taken aback. He had expected some reaction from Gautama regarding Pilotika’s praise. Some boasting maybe, or some humility, anything…

But Gautama simply began to teach. He said:

‘If an elephant hunter enters a forest he might see a large elephant footprint. But if he is a skilled hunter, he will not conclude there is a large bull-elephant in the forest. A skilled hunter would know there are small elephant females with exceedingly large feet. The footprint could be one of theirs.

‘So, the skilled hunter follows the footprint into the forest.

‘There he might find three more footprints, and scratch marks, and tusk slashes, and some broken off branches. Still, he will not conclude there is a bull-elephant in the forest. A smaller elephant could have left those.

‘But if the hunter continues following the tracks, he might arrive at a bull-elephant at the foot of the tree or in an open clearing. Only then does he conclude there is a bull-elephant.’

Let’s pause again.

First-Hand Truth

How has the Buddha improved Pilotika’s simile?

Well, we see in Pilotika a somewhat superficial form of spirituality. You know, the kind where one hears or reads something and decides immediately it is the ultimate truth. Lesser teachers welcome such easy converts.

The Buddha, however, would have none of that.

His extended simile tells us we shouldn’t be satisfied with outer appearances. A footprint is not enough. We should actually enter the forest ourselves, follow the tracks and make sure we see the truth with our own eyes. We should settle for nothing less than the actual elephant.

And here we arrive at the Noble Eightfold Path.

We will hear now the Buddha describe the full journey of the early Buddhist disciple. But I have to warn you…

The Path To Mastery

It is easy to get discouraged when you hear what dedication the Buddha expects of us. It is one thing to meditate for letting off steam – it is a whole different game to leave your family and friends in search of awakening.

The Path to nirvāṇa can sometimes sound so demanding as to be totally out of reach.

But imagine Gary Kasparov comes to teach you chess, or Arnold comes to teach you weight-lifting. You wouldn’t get discouraged. You wouldn’t compare yourself to the master. You would try to learn a thing or two that will serve your own improvement.

This is a good way to approach the Buddha’s teachings too.

As ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi says, there are only two things you must do on the path. You must start and you must continue.

With this in mind, let’s now hear the Buddha describe the Path to Janussonin.

Right View & Right Intention

‘A self-awakened teacher appears in the world,’ Gautama continued. ‘He teaches the Dhamma in detail and in essence. A householder, upon hearing the Dhamma, reflects on his own life. He sees how difficult it is to live at home a holy life perfect as a polished shell.

‘After much deliberation, he decides to abandon his wealth, be it great or small. He leaves his relatives and friends, shaves, puts on a robe, and enters a life of homelessness.’

No wonder, the early schools of Buddhism came to be called Hīnayāna, or the small vehicle. The original Buddhist path was not for the many, but for the few. For a spiritual elite, an aristocracy even. Notice how often the adjective ‘noble’ is used for the doctrines.

Of the Four Noble Truths, you can learn in a previous article.

In any case, our path begins with Right View and Right Intention, the Wisdom section of the path. The seeker receives this wisdom upon his or her encounter with the Dhamma. The wheel has been turned and no matter how long it takes, the seeker is now on a trajectory to nirvāṇa.

The Buddha continues with the following stages of the Path.

Right Speech, Right Action & Right Livelihood

‘Once the seeker becomes trained in the life of a monk, he begins to cultivate virtue.’

‘He abandons the taking of life and cultivates compassion for all living beings.’

‘He abandons the taking of what is not freely given.’

‘He abandons sex, a commoner’s practice.’

‘He abandons speech that is false, divisive, abusive, or idle. On the contrary, he cultivates speech that is true, that brings harmony, that heals those who hear it, and that concerns only what is important.’

‘He abstains from violence, even to plant life.’

‘He eats only once per day.’

‘He avoids all entertainment.’

‘He abstains from beautifying himself with jewellery, perfumes, and the like.’

‘He avoids unnecessary comfort.’

‘He accepts no money.’

‘He is content with a set of robes to provide for his body and alms food to provide for his hunger. A bird, wherever it goes, flies with its wings as its only burden. So too, wherever he goes, the seeker takes only his barest necessities along.’

Buddhist Renunciation

Suffice it to say, the Noble Path does not start easy. It is a life of abstinence and privation. Still, I think it is a happy life.

Today we have more wealth, luxury, and comfort than ever. At the same time, stress, depression, and suicide are at a peak. Today’s researchers keep ‘discovering’ the benefits of healthy discomfort. The Buddha, of course, spoke about this over two millennia ago.

There’s another important point.

The renunciation taught by the Buddha is not based on suppression. In many traditions, asceticism is meant to strengthen the will through inner conflict with one’s natural impulses. We can see this most clearly where the ascetic would literally mutilate his body in order to ‘overcome’ it, whatever that means.

This is something the Buddha tried also. He discovered it does not lead to awakening and liberation. In fact, he said trying to overcome the body is the easiest way to become obsessed by it.

Instead, Buddhist renunciation is based on mindfulness, understanding, and transformation. The end goal is not to become stronger than your instincts and desires. It is to understand them and their consequences. To separate what causes suffering from what alleviates suffering. After that it is just a matter of navigating towards thoughts, words, and actions that lead to the cessation of suffering.

The Inner & Outer Path

Anyway, the Buddha has now described Right Speech, Right Action, and Right Livelihood. This is the Ethics section of the path. It ensures a harmonious life in the world and among others.

But the real purpose of these precepts is psychological and inward-looking. The simple, ethical life is in fact a form of mental preparation.

First, you cultivate discipline and mindfulness in the world outside. Next, you apply these to your body and your sensory experience. After that, you sink even deeper and practice discipline and mindfulness of your mental states. Finally, you go beyond the mental and enter the most subtle dimensions of experience.

If we remember the elephant hunter going deeper into the forest, we will see how accurately it describes the Path. Each stage prepares the seeker for the following one; each takes him deeper into himself.

Let’s return to the story now where the Buddha will describe the next stages of the Eightfold Path.

Right Effort, Right Concentration & Right Mindfulness

Gautama continued:

‘The seeker cultivates restraint of the senses. Upon seeing a form, or smelling a smell, or hearing a sound, or tasting a flavour, or sensing by touch, or thinking a thought – he never grasps at the experience. He develops no interest in the experience that might lead to attachment. He notices that whenever he is unmindful of his senses, desire arises. After desire, discomfort and suffering follow.’

‘Therefore, the seeker cultivates mindfulness.

‘He is aware always of his posture and the movements of his body. At all times, whether eating or defecating, working or resting, he is mindful. Whether he speaks or is silent, awakes or falls asleep, whether standing, or sitting, he is always present and aware.’

‘Having perfected his livelihood, speech, and actions, having cultivated restraint and mindfulness – the seeker finds a secluded spot. After his meals, he retreats to that place. He sits down, crosses his legs, holds his body erect, and devotes himself to mindfulness.’

‘He encounters the five hindrances and overcomes them one by one.’

‘He is attacked by desire – but he lets go of it.’

‘He is attacked by anger and ill-will – but he overcomes them through compassion.’

‘He is laid down by drowsiness, but he cuts through it with alertness.’

‘Anxiety and restlessness appear, but he stills his mind.’

‘Doubt and uncertainty cloud his judgement, but he abandons them.’

‘Finally, with his mind ready, he enters the first jhana.’

Let’s pause again.

The Path Beyond The Self

In another sutta, the Buddha compares the untrained mind to a fish out of water, flapping about on the ground. We chase after thoughts, sensations, and emotions, as if the next one will bring us what we desire. Such a mind lacks the mindfulness and concentration needed for true insight.

But say we have disciplined our mind. Say we have developed mindfulness. We overcome the five hindrances… then what?

Well, then we are ready for the last and most advanced stages of the path. We arrive at Buddhist meditation proper.

Here describing the path gets difficult.

It gets difficult because the Buddha describes altered states of awareness accessible to seasoned meditators. The first of these are the four jhanas. Since most of us have no experience with these states, it is easy to either dismiss them or adopt a completely wrong view of them.

To avoid this error, I will quote the Buddha without trying to interpret him. So, back to the story.

Right Effort, Right Concentration & Right Mindfulness (Cont.)

Gautama continued.

‘The seeker enters and remains in the first jhana. He experiences the delight of withdrawal, accompanied by directed thought and evaluation. This is like a large elephant footprint, but still, it is early to conclude there is a bull-elephant in the forest.’

‘Then, as directed thoughts and evaluations subside, the seeker enters and remains in the second jhana. He experiences the delight of composure and one-pointed awareness. There is no longer directed thought and evaluation. This too is a large footprint, but still no elephant.’

‘With the fading of delight, the seeker enters and remains in the third jhana. He is at peace, mindful, and alert, and senses pleasure with the body. This is the third elephant footprint.’

‘Finally, with the abandoning of pleasure and pain, the seeker enters and remains in the fourth jhana. He experiences peace and mindfulness, without either pleasure or pain. This is the fourth elephant footprint.’

‘Even now, the experienced hunter does not conclude there is a bull-elephant in the forest. He does not conclude that Gautama is truly self-awakened, that he teaches the true path correctly, and that his disciples practice rightly.’

A Special Experience Is Not The Goal

Notice how the Buddha continuously warns us not to grasp at sublime states of consciousness. Remember this whenever you yourself become fascinated by a spiritual experience. That experience might be a beautiful step along the path, but do not confuse it with the destination.

Anyway, the Path now seems complete.

We started with Right View and Right Intention where the seeker understands he must devote himself to the Dhamma and does so. This is the Wisdom section of the path, activated upon contact with the Dhamma.

We continued with Right Speech, Right Action, and Right Livelihood. This is the Ethics section, the outer expression of the path.

Finally, we arrived at Right Effort, Right Concentration, and Right Mindfulness. This is the section of Mental Discipline where the path turns inward.

So, if all elements are present, why does the Buddha say the seeker has still not discovered the bull elephant?

Well, because the path is not a line – it is a circle. Like any circle, it is complete only when the end meets the beginning.

The Three Higher Knowledges

After passing all stages, the seeker returns to the Wisdom section. However, this time he does not receive wisdom second-hand. He experiences the Dhamma himself.

This is known as the Three Higher Knowledges. These are experiences of insight accessible only to a mind that has been trained and purified to perfection.

It is difficult to make sense of these experiences. It is much easier to label them as supernatural or dismiss them as hallucinations. But I think we should refrain from judgement.

The truth is, we are unqualified to draw any conclusions about the Higher Knowledges. To do so would be like a young child thinking she knows what being an adult is like.

Without having walked the path leading to the Knowledges, it is best to remain critical, but open-minded.

In any case, this final section of the path culminates in direct insight into the Four Noble Truths. Remember, the last of these Truths is the Noble Eightfold Path itself. So, the Truths contain the Path and the Path contains the Truths! Together, they complete the wheel of the Dhamma where practice must be wise and wisdom must be practiced.

Now we will end with the Buddha. Here is how he describes the completion of the Path:

The Task Is Done

‘With his mind concentrated, purified, and bright, the seeker directs it to the recollection of past lives. He remembers one birth, two births, three births, a hundred thousand births… He realizes ‘There I had such a name and such an appearance. Such was my experience and such the end of my life. Passing away from that state, I re-arose in another.’ In this way he recollects his many past lives in detail.’

‘With this insight, his divine eye opens. He sees beings passing away and re-appearing, and he discerns how they are inferior and superior, beautiful and ugly, fortunate and unfortunate in accordance with their karma. He sees how beings with Wrong View and Wrong Action get reborn in planes of deprivation. He sees how beings with Right View and Right Action get reborn in heavenly worlds. He sees all this cycle and the law of karma that rules it.’

‘Finally, the seeker discerns through direct experience the Four Noble Truths. He comprehends dissatisfaction and he comprehends the way leading to dissatisfaction. He comprehends nirvāṇa and he comprehends the way leading to nirvāṇa.’

‘All these are also like large elephant footprints. Still, the seeker does not conclude there is a bull-elephant in the forest. He does not conclude Gautama is truly self-awakened and teaches the true path correctly, and his disciples practice rightly.’

‘But his heart and mind, having gained wisdom, become free from craving, free from becoming, and free from ignorance. With this freedom, he realizes ‘Birth is ended, the holy life is fulfilled, the task is done. Nothing remains for this world.’

‘This is the large bull-elephant. Only now does the seeker understand Gautama is truly self-awakened, he teaches the true path correctly, and his disciples practice rightly.’

There was silence when the teacher stopped speaking.

Janussonin too was silent. Only the burble of a nearby stream could be heard.

Whatever the brahman felt at that moment, he would never forget it.

He bowed before the teacher and said: ‘Blessed One, please remember me as one who has come to you for refuge. From now on until the rest of my life.’

Hello, the text is wonderful and beautiful.

Thank you, Ryath, I appreciate you taking the time to comment 🙂